Concurrency is more about achieving thread-safety, than it is about creating & managing threads. Those are mechanisms, but at its core, concurrency aims to encapsulate shared mutable state from uncontrolled concurrent access.

State of an object

An object’s state encompasses any data that can affect its externally visible behavior. An object’s state is its data, stored in state variables such as instance or static fields.

An object’s state may include fields from other dependent objects. Example a HashMap’s state is partially stored in the Hash Map object itself, but also in many Map.Entry objects.

Shared Variable: could be accessed by multiple threads.

Mutable: Value could change during its lifetime.

Thread safety

Thread-safety is about trying to protect the data from uncontrolled concurrent access. Whether an object needs to be thread-safe depends on whether it will be accessed from multiple threads. This is a property of how an object is used in a program and not what it does.

Making an object thread-safe requires using synchronization to coordinate access to its mutable state. Failing to do so could result in data corruption and other undesirable consequences.

When more than one thread accesses a given state variable and one of them might write to it, they all must coordinate their access to it using synchronization.

The primary mechanism for synchronization in Java is the synchronized keyword, which provides exclusive locking, but the term ‘synchronization’ also includes the use of

1)volatile variables

2) Explicit locks

3) Atomic variables

If multiple threads access the same mutable state variable without appropriate synchronization, the program is broken and there are three ways to fix it:

- Don’t share the state variables across threads.

- Make the state variable immutable.

- Use synchronization whenever accessing the state variable.

If it easier to design a class to be thread-safe than to retrofit it for thread safety later.

Object oriented techniques can help write well-organized, maintainable classes - such as encapsulation and data hiding - can also help create thread-safe classes.

Java does not force developers to encapsulate state - A state can be stored in public fields or public static fields or publish a reference to an otherwise internal object, but the better encapsulated the program state is, the easier it is to make the program thread-safe. The less code that has access to a particular variable, the easier it is to ensure that all of it uses proper synchronization.

When designing thread-safe classes, good object-oriented techniques - encapsulation, immutability and clear specification of invariant are helpful.

Invariant means something that should stick to its conditions no matter whatever changes or whoever uses/transforms it.

There might be times when good OO design techniques are at odds with real-world requirements.

- Rules of good design need to be compromised for the sake of performance or for the same of backward compatibility with legacy code.

- Abstraction and Encapsulation are at odds with performance - (although not nearly as often).

It is a good practice to make the code right and then make it fast. Pursue optimization only if needed and those same measurements tell you that your optimizations actually made a difference under realistic conditions.

A program that consists entirely of thread-safe classes may not be thread-safe. The concept of a thread-safe class makes sense only if the class encapsulates its own state.

What is Thread Safety?

The heart of any reasonable definition of thread safety is its concept of correctness.

Correctness means that a class conforms to its specification. A good specification defines in-variants constraining an object’s state and post - conditions describing the effects of its operations.

If an object is correctly implemented, no sequence of operations - calls to public methods and reads or writes of public fields - should be able to violate any of its invariant or post-conditions.

No set of operations performed sequentially or concurrently on instances of a thread-safe class can cause an instance to be an invalid state.

Frameworks like servlet frameworks create threads and call components from those threads, leaving developers with making the components thread-safe.

Stateless servlet

| |

StatelessFactorizer in the above example has no fields and references no fields from other classes.

The transient state for a particular computation exists solely in local variables that are stored on thread’s stack and are accessible only to the executing thread.

One thread accessing a StatelessFactorizer cannot influence the result of another thread accessing the same StatelessFactorizer because two threads do not share state. It is as if they were accessing different instances.

Since the actions of a thread accessing a stateless object cannot affect the correctness of operations in other threads, stateless objects are thread-safe.

If its only when servlet wants to remember things from one request to another that the thread safety requirement becomes and issue.

Atomicity

Adding one element of state to a stateless object would make it not thread-safe, even though it worked just fine in a single-threaded environment.

In this example, a variable count is introduced to keep track of the number of request processed. Though this may work just fine in a single threaded environment, it is susceptible to lost updates.count variable as noted previously, despite its shorthand syntax has 3 discrete operations (read-modify-write operation).

- Fetch the current value.

- Add one to it.

- Write the new value back.

| |

If two threads increment the counter simultaneously, without synchronization, the counter would not give an accurate result. The possibility of incorrect results in the presence of unlucky timing is called a race condition.

Race conditions

A race condition occurs when the correctness of the computation depends on lucky timing (relative timing or interleaving of multiple threads by runtime).

check-then-act

check-then-act is a type of race condition that uses a potentially stale observation to make a decision or perform a computation. The observation could have even become invalid between the time it was observed and the time an action was take on it.

Example: Lazy initialization

| |

The goal of lazy initialization is to defer initializing an object until it is actually needed at the same time making sure that it is initialized only once.

The getInstance() method checks whether the expensive object has been initialized, in this case it returns the existing instance, otherwise it creates a new instance and returns it retaining a reference so that it can be used for future invocations (to avoid expensive code paths).

When two threads A and B execute getInstance() at the same time. ‘A’ sees that instance is null and initiate a new object. ‘B’ also checks if instance is null. The state of instance depends on

- Timing (which is unpredictable)

- Vagaries of scheduling

- How long A takes to initiate the

ExpensiveOjectand set the instance field.

‘B’ may again initialize a new instance even though getInstance() was supposed to return the same instance.

Race conditions does not always result in failure but can cause serious problems. As an example, different instances from multiple invocation could cause registrations to be lost or multiple activities to have inconsistent views of the set of registered objects.

read-modify-write

As we saw previously ++count is not an atomic operation. To properly increment the counter, the current thread must know its previous value and make sure no other thread is changing or using the value in the middle of the update.

Compounded Actions

Both read-modify-write and check-then-act (collectively referred to as compound actions) contains a sequence of operations that need to be atomic or indivisible, relative to other operations on the same state (i.e) sequences of operations that must be executed atomically in order to remain thread safe.

To avoid race conditions, there must be a way to prevent other threads from using a variable while we are in the middle of modifying it, so we can ensure that other threads can observer or modify the state only before we start or after we finish but not in the middle.

An atomic operation is one that is atomic with respect to all operations, including itself, that operate on the same state.

Operations A and B are atomic with respect to each other if, from the perspective of a thread t1 executing operation A, when another thread t2 executes B, either all of B has executed or none of it has.

The CountingFactorizer can be made atomic by using java.util.concurrent.atomic package that contains atomic variable classes for effecting atomic state transition on numbers and object references.

By replacing the long counter with an AtomicLong, all actions that access the counter state are atomic. Because the state of the servlet is the state of the counter and the counter is thread-safe the servlet is once again thread-safe.

Locking

Adding one more thread-safe state variable to the class will not make it thread-safe

The definition of thread safety requires that invariant be preserved regardless of timing or interleaving of operations in multiple threads.

| |

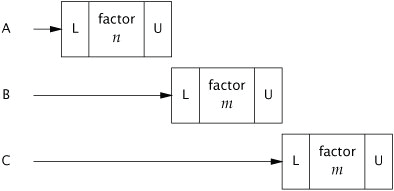

The above example is responsible for improving the performance of the servlet by caching the most recently computed result, just in case two consecutive clients request factorization of the same number. To implement this, the last number factored and its factors needs to be remembered.

Using atomic references, both lastNumber and lastFactor cannot be updated simultaneously. Even though each call to set is atomic, there is still a window of vulnerability when one has been modified and the other has not, and during that time, other threads could see that the invariant does not hold. Similarly, two values cannot be fetched simultaneously, between the time when thread A fetches the two values, thread B could have changed them and again A may observe that the invariant does not hold.

Reentrancy

Reentrancy means that locks are acquired on a per-thread rather than per invocation basis.

When a thread requests a lock that is already held by another thread, the requesting thread blocks. But since intrinsic locks are re entrant, if a thread tries to acquire a lock that it already holds, the request succeeds.

Reentrancy is implemented by associated each lock with an acquisition count and an owning thread.

When a thread acquires the lock (previously unheld lock) the JVM records the owner and sets the acquisition count to 1. If the same thread acquires the lock again, the count is incremented and when the owning thread exists the synchronized block the count is decremented. When the counter becomes zero, the lock is released.

Reentrancy facilitates encapsulation of locking behavior and thus simplifies the development of object-oriented concurrent code.

| |

In the above example calls to the super class method would deadlock without re-entrant locks. Re-entrancy saves us from this deadlock situation.

Guarding state with locks

Because locks enable serialized access (Serializing access means threads take turns accessing the object exclusively, rather than doing concurrently) to the code paths they guard, we can use them to construct protocols for guaranteeing exclusive access to the shared state.

Compound actions on shared state such as incrementing hit counter (read-modify-write) or lazy initialization (check-then-act) must be atomic to avoid race conditions.

Just wrapping the compound action with a synchronized block is not sufficient.

- If synchronization is used to coordinate access to a variable, it is needed everywhere that variable is accessed.

- When using locks to coordinate access to a variable, the same lock must be used wherever that variable is accessed.

A common locking convention is to encapsulate all mutable state within an object to protect it from concurrent access by synchronizing any code path that access mutable state using the object’s intrinsic lock. It is easy to subvert this locking protocol accidentally by adding a new method or code path and forgetting to use synchronization.

Adding synchronization to every method is not enough. For example, put-if-absent operation has a race condition, even though both contains and add are atomic (When multiple operations are combined into a compound action).

| |

At the same time, synchronizing every method can lead to liveliness or performance problems.

Liveness and Performance

It is easy to improve the concurrency of a component while maintaining thread safety by narrowing the scope of synchronized block. However, the scope of the synchronized block should not be too small - an atomic operation should not be divided into to more than one synchronized block.

It is reasonable to exclude long-running operations that do not affect shared state so that other threads are not prevented from accessing the shared state while the long-running operation is in progress.

| |

The above example has race conditions.

| |

In the above example, the servlet caches the last result but has unacceptable concurrency. Only one thread can use the servlet at a time, defeating the purpose of using servlets.

| |

By narrowing the scope of the synchronized block, concurrency of the servlet can be improved while maintaining thread safety.

The above example uses two synchronized block, each limited to a short section of code.

- One guards the

check-then-actthat tests whether we can just return the cached result. - The other guards the update of cached number and the cached factors.

The portions of code that are outside the synchronized blocks operate exclusively on local variables, which are not shared across threads and therefore do not require synchronization.

Acquiring and releasing a lock has some overhead, so it is undesirable to break down synchronized blocks too far (even though it would not compromise atomicity).

CachedFactorizer holds the lock when accessing state variables and for the duration of compound actions but releases it before executing the potentially long-running factorization operation. These preserves thread safety without affecting concurrency.

Holding a lock for a long time, either due to compute-intensive tasks or due to a blocking operation, introduces the risk of liveliness or performance problems.

Avoid holding locks during lengthy computations or operations at risk of not completing quickly such as network or console I/O.